COFFEE CHEMISTRY & ACIDITY

A ROAST & BREW GUIDE

A ROAST & BREW GUIDE

One of the most prized attributes and one of the most misunderstood, ‘acidity’ adds dimension to coffee. To a certain extent, acidity is inherent to a coffee but the way it’s perceived can be changed by the way it’s roasted and the way it’s brewed. Let’s zoom in on this savoury yet controversy topic.

I. FROM A SCIENTIFIC POINT OF VIEW – COFFEE ON THE PH SCALE

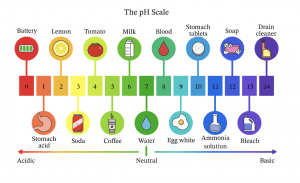

People often confuse the scientific description of acidity with the coffee tasting description of acidity. In science, acidity is rated on a pH scale. On this scale, a pH of 7.0 is considered neutral which means that the positive and negative ions in the water are in equal levels and essentially cancel each other out. If a substance is acidic, it has a low pH. For example, lemon juice is acidic and has a pH of 2.0. When it’s added to neutral water, it will release hydroxide ions, thus lowering the pH.

At the opposite end of the scale, soapy water has a pH of 12 and is ‘basic’ (read: the opposite of acidic) – soap, when added to water, releases hydrogen ions making it ‘basic’. The presence of acids in coffee will lower its pH, therefore the pH of coffee tends to vary but it’s generally around 4.5.

| → Coffee often gets branded as an acidic drink, but in fact, coffee comes in at around a five on the pH scale, which is actually less acidic than drinks like beer, orange juice, and even soda. |

II. FROM A SCIENTIFIC POINT OF VIEW – ACIDS FOUND IN COFFEE

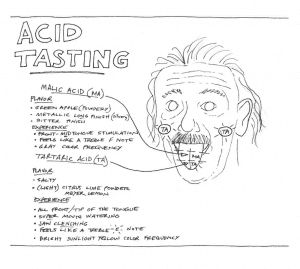

The acidity in coffee itself can range from the crisp acidity of an apple (Malic acidity) to the grape-like (Tartaric acidity) which makes your mouth water (think ‘Tangfastics’ – Haribo’s sour coated gummies), to the vinegary (Acetic acid) or the sharpness of citrus (Citric acid).

Too much of any of these can lead to a bad experience. ‘Malic’ acidity can give an astringent, unripe fruit aspect and ‘Acetic’ can give off funky or fermented tastes. However, when they are in balance, and in the presence of sugars (the natural sweetness in a good coffee), then that vinegar experience can turn in to wine-like or champagne-like experience.

Let’s focus on the ones that survive the roasting process*, as they are the acids that affect a coffee’s final flavour. The first ones listed below have a positive impact on a coffee, while those lower on the list can have good and bad effects.

°Citric acid is found in arabica beans grown at higher elevations. The same acid that’s found in citrus fruits, this acid is associated with notes of lemon, orange and, when occurring with phosphoric acid, grapefruit.

°Phosphoric acid tastes sweeter than most acids. It can turn an otherwise sour-tasting citrus flavour into a sweeter grapefruit- or mango-like one.

°Malic acid is sometimes associated with hints of stone fruit, such as peaches or plums, but it’s more common to taste apple or pear in a coffee that has malic acid.

°Chlorogenic acids (CGAs) are largely responsible for a coffee’s perceived acidity. Compared to other acids, they degrade rapidly in the roasting, which is why light roasts are described as “bright” and “acidic” more often than dark ones.

°Acetic acid, which is the same acid that’s found in vinegar, may produce a pleasant sharpness at lower concentrations. Higher levels of acetic acid, though, are unpleasant. A coffee that has a lot of acetic acid probably wasn’t properly processed.

°Tartaric acid, similarly, produces a sour taste at high concentrations. At low levels, however, it can offer up grape-like or winey notes, which isn’t surprising since it’s found in grapes.

°Quinic acid is produced as other acids degrade. High concentrations of it are common in darkly roasted coffee, stale coffee, and coffee that was brewed several hours ago but kept warm on a hot plate. Although it gives coffee a clean finish, quinic acid is the main acid that turns stomachs sour.

→ Many of the tastes you identify in coffee can be directly attributed to the acids contained within them. If you can identify acids you prefer, then you’ll be able to look for coffees that have been grown or roasted in a way likely to produce those acids.

III. FROM A SENSORY & SEMANTIC POINT OF VIEW – COFFEE ACIDITY LINGO

In coffee (and other food and drink generally), we think of acidity in terms of our sensory experience. Acidity is one of the key components of how a coffee tastes. The word can be a little confusing, however, as usually when we are referring to food, acidic isn’t usually a desirable quality. But that’s not the case when talking about acidity in coffee, because here, acidity is a desirable quality. In fact, when coffee professionals talk about ‘acidity’, they are talking about the presence of certain acids that influence the taste of coffee. Acidity doesn’t refer to the actual acid content — it refers to a flavour note.

The easiest way to understand coffee acidity is to think of it as an abstract concept. ‘Lemon acidity’ doesn’t mean that your coffee literally tastes like lemons. Its true meaning is something closer to ‘it is as sour as an lemon’.

When sipping a coffee with higher acidity, you should experience a smooth, dry, sharp, pleasantly tart, tingling snappy sensation at the tip of your tongue, similar to what you may experience after eating an orange or sipping a lemon-flavored drink. This strong, bright, clean, almost tingling sensation is a hallmark of higher acidity coffee. While you don’t necessarily taste lemon or orange in your coffee, your mouth and senses react as if you had. As acidity levels in coffee drops, the tingling sensation gives way to a juicier, wetter feeling in the mouth with lower acidity coffees providing a long, almost textured close or aftertaste.

Since ‘acidity’ is used to talk about how coffee tastes, you may have heard this flavour note referred to in other ways; with words that are a bit more indicative of the taste itself, such as ‘lively’, ‘spicy’, ‘sharp’, ‘bright’, ‘juicy’, ‘sparkling’,… If you understand the general meaning of what the term means, we might conclude that it describes to us how ‘alive’ or ‘awake’ the coffee is.

→ High acidity coffees are often described as clean, bright, lively, light, crisp and/or vibrant with light or moderate mouthfeel.

→ Low acidity coffees are often described as smooth, silky, juicy, creamy, dense and/or mild with moderate to heavy mouthfeel.

Mané Alves -Founder of Coffee Lab International, Q instructor, international tasting judge, and the former Director of SCA Technical Standards Committee- took a spot-on approach to this subject, and we would like to quote him below:

°Origin: Each origin has a ‘certain soil type and a certain amount of a certain acid’. For example, malic acid is more common in Kenyan coffee, while citric acid is more common in Colombian coffee. That means more apple notes from Kenya and more citrus fruits from Colombia.

°Variety & Species: This plays an important role in the perceived acidity of your cup of coffee. For example, the Arabica variety tends to have less chlorogenic acids, which decreases the perceived acidity. Certain varieties, such as the SL-28 found in Kenya, are more acidic. Part of this is simply genetics. But part of it is also due to agricultural conditions. Certain varieties are more suited to growing at lower temperatures than others – and that also affects the taste.

°Climate & Altitude: The most coveted coffee beans are usually grown at higher elevations, but this has more to do with temperature than altitude. Coffee grown at lower temperatures tends to mature more slowly, allowing for more complex flavours. When brewed, it tends to be more acidic and aromatic than coffee grown in warmer climates, for example lower down the same mountain. Coffee varieties can “generate more acidity if planted at the right height.”

| °Processing: While we often call coffee a bean, this is a lie: it’s the seed of a sweet, flavourful berry known as a cherry. But removing this fruit is tricky. There are several ways to do this and the method chosen will affect the final taste. For example, wet/washed coffees are pulverized and rinsed in water, removing the layers of sucrose and fructose. This allows the acidity to come into its own, unfiltered by that sweetness. On the other hand, naturally processed coffees leave the fruit intact while the coffee dries, increasing the overall sweetness and overpowering the perceived acidity. |

→ If you want to avoid acidity altogether, you should start with coffee with a very low acidic content.

→ No matter how you brew or roast them, some coffees will always be more acidic than others. factors such as origin, variety, processing method and climate have a huge influence on this.

For this we would like to quote the insights that Verônica Belchior – biologist, Master in Ecology, PhD in Food Sciences, Q-grader & teacher and Mané Alves shared in previously published professional contribution.

‘During roasting or brewing you cannot create a taste that a coffee does not have. However, you can roast it in a way that accentuates or obscures the acidity. First, you can consider the roast level. Most acids decrease in concentration during the roasting process, and some others [acids] are created by the breakdown of the compounds – chlorogenic acids can be broken down into the bitter quinic acid and caffeic acid. The lighter a roast, the more the coffee’s natural flavours will be present in the cup (although, of course, you don’t want to roast so lightly that the brew becomes sour or grassy). The darker the roast, the more likely these flavours are hidden under more roasty or even bitter flavours’.

‘Dark roasting without causing bitterness is an art. But roasting isn’t just about how long you keep the beans in the roaster. It’s about how you manipulate the heat and airflow to enhance the best features of the coffee. High heat tends to strip the acidity. Be careful not to go too high and scorch your coffee. You want the perfect balance, taking into account the type of beans you have. The softer the bean -which is often associated with higher farm temperatures- the more gentle you need to handle the heat.’

‘Your goal should be an early first crack that doesn’t last too long – something that goes hand in hand with high heat. But don’t forget, too early or too short also leads to acidification.’

→ Know your beans – You can only accentuate the characteristics that are already in your coffee beans. For that reason it is important to know what you have on your hands.

→ ‘Timing is key’ meets ‘Balancing Act’ – There is a small time-window, and if you catch it just right, the coffee is unlocked with complex fruity flavours, a pristine acidity and dimension.

→ Practice makes Perfect – Try roasting and cupping your coffee with different brewing times and profiles. This should give you a better understanding of how your roast profile affects the acidity of the coffee. The more you do this, the more insights you get.

To get the best flavours from a coffee, you need the right level of extraction. Understanding how this happens can allow you to troubleshoot if your coffee doesn’t taste right. In almost every method of preparing a coffee – be it espresso, pour over, cold brew, or french press – the general principle is the same. Take the roasted coffee, grind it into small pieces, and add water. Once the water hits the coffee, it starts to extract out the flavour compounds.

The degree of extraction will affect the flavours and aromas in the cup, since not all compounds are extracted at the same time. Fruity and acidic notes are extracted first, followed by sweetness and balance, and then finally bitterness.

Under-extracted coffee won’t have the sweetness and slight bitterness needed for balance, and will have a sour taste. An over-extracted brew will taste bitter, as the compounds that create sweetness and acidity will be overwhelmed.

Check out these tips to control acidity in brewing coffee.

- Grind Size – The finer the grind size, the more quickly extraction happens (remember: extraction time is different to brew time). A coarse grind size means more acidity; a fine grind size, more bitterness.

- Brew Time – The longer the brew time, the more time extraction will happen. Short brews are more acidic; longer ones, more bitter.

- Water* Temperature – The hotter the water, the more quickly the extraction will happen – but too cool a water temperature and the acids won’t extract. Mané says, “We can create good acids and bad acids while brewing… using hot water will generate a much higher acid formation on the brewing cup than using cold brew (one of the cold brew characteristics is a very mellow acid presence).” 90-95°C

→ Finer grind size extracts oil faster, making a cup of coffee bitter. Adjust your coffee grounds coarser for acidity.

→ Longer brew time makes a cup of coffee bitter. Make shorter brew time for more acidity.

→ A quicker extraction happens when introducing a hotter water temperature. Increase water temperature if you want more acidity in your cup of coffee.

Acidity is an complex subject, with many factors affecting its presence or absence in a beverage. However, selecting and brewing a coffee that suits your personal preferences doesn’t have to be so complicated.

- Coffees with a hint of ‘citric acidity’

° Kenya, Kirinyaga – Top Kiri

° Colombia, Huila – Finca El Diviso

- Coffees with a hint of ‘malic acidity’

° Ethiopia, Guji – Goro Muda

° Burundi, Muyinga – Inzahabu Mukingiro

- Coffees with a hint of ‘acetic acidity’

° Costa Rica, Tarrazu – Finca Francisco Molina

° Costa Rica, San José – Finca Las Lajas

KUDO’S, INSPIRATION & REFERENCES

Perfect Daily Grind – Why are some Coffees more Acidic than Others

Academia – Acidity in Coffee : Bridging the Gap Between Chemistry & Psychophysics

Healthline – Is Coffee Acidic ?

The Queen Been – The Breakdown: Acidity in Coffee

Cuprima – Coffees

* Water Quality – As you might know a cup of coffee is actually 98 % water. So it’s a no-brainer that higher quality water makes your coffee taste better !